What To Expect From The FOMC Statement And Powell's Speech Today?

The first is always the hardest, and for the US Federal Reserve, its first FOMC meeting this year definitely fits this saying, especially considering trying to convey the right signal to the world in a complicated market environment.

When exactly will the interest rate be cut? And by how much?

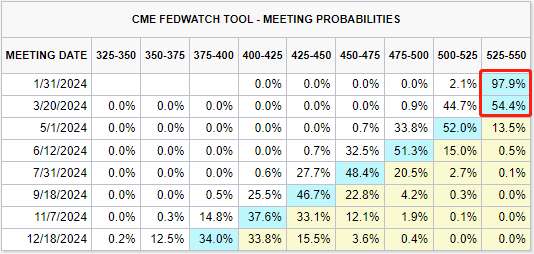

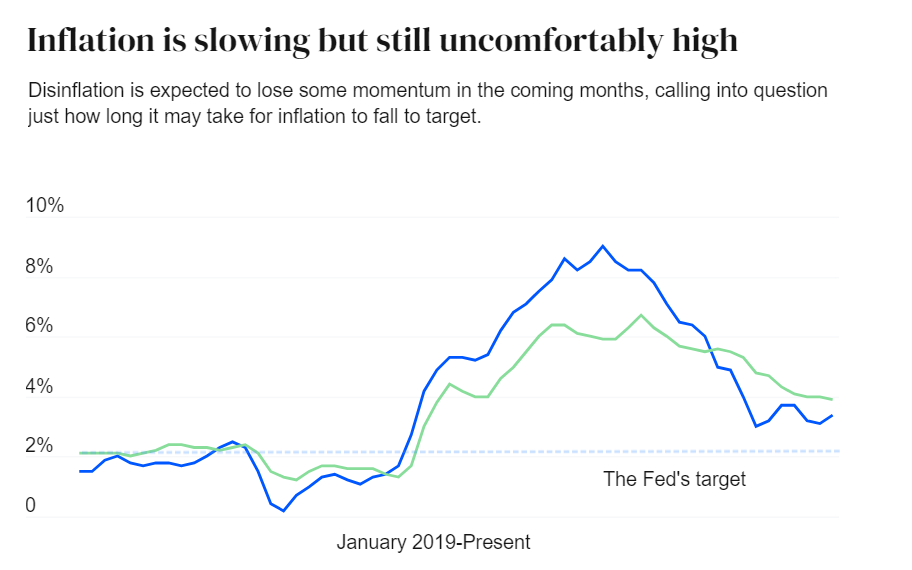

As a matter of fact, since the rate decision in December, with the continuous downplaying of rate cut expectations by Fed officials and the unexpected rebound of some macroeconomic data, including the Consumer Price Index (CPI), market expectations of a rate cut by or in March have considerably waned.

According to Fed Watch data, for the interest rate decision in January, the markets have firmly believed the Federal Reserve will hold the current rate for a fourth consecutive meeting. The probability of a rate cut in March has dwindled to 45%.

However, this does not mean that the widespread optimism on interest rate cuts has changed significantly: the market still expects the Fed to cut rates at least 5 times this year, with many people predicting up to 6 or even 7 rate cuts. In fact, even notable analysts from institutions such as Goldman Sachs and Bank of America also hold similar views.

Furthermore, even though both Bostic and Waller have repeatedly stressed that the Fed will not be hasty in action with regard to rate controls, many people still expect the Fed to possibly cut interest rates by up to 1 percentage point from May to the end of the year. Some even suggest that a 1.5% cut in interest rates seems plausible.

However, over the past 44 years, the Federal Reserve has only once lowered rates by 1.25 percentage points or more within a year. Still, many seem unfazed by the likelihood of this happening.

Will Powell be more specific this time?

While there's consensus that the Fed will not make changes to interest rate levels at this FOMC meeting, Powell's speech after the meeting will still be widely noted and interpreted.

According to Wall Street estimates, Powell might not disclose too much vital information this time, unlike the last time when he implied Interest cuts have begun to come into view. However, it's worth noting that this first meeting of the year marks a fresh batch of regional Fed presidents gaining voting power.

These include Loretta Mester of the Cleveland Fed, Thomas Barkin of the Richmond Fed, Raphael Bostic of the Atlanta Fed, and Mary Daly of the San Francisco Fed. This group largely consists of those officials with the most staunch opposition to interest rate cuts.

As a result, even though there might not be much valuable information being released, Powell's upcoming speech is likely to be more hawkish than previous ones,

Meanwhile, the Fed may make some minor changes to statements following the meeting. For instance, in the new easy monetary policy statement, there likely won't be any terms, suggesting tightening bias—which usually indicates that the probability of future rate hikes is higher than that of rate cuts. After the meeting in December, nearly all Fed officials stated that there's no need for another rate hike, so there's no need to use such potentially confusing expressions.

In effect, that's saying that they're more likely to be raising than cutting, as expressed by Bill English, former head of the Fed's Monetary Affairs Division, now a professor of finance at Yale, when explaining this change. I guess they don't think that's really true. So I would think they'd want to be ready to cut rates in March if it seems appropriate when they get there.

Interest rates remain the same, but further reductions in the balance sheet are uncertain.

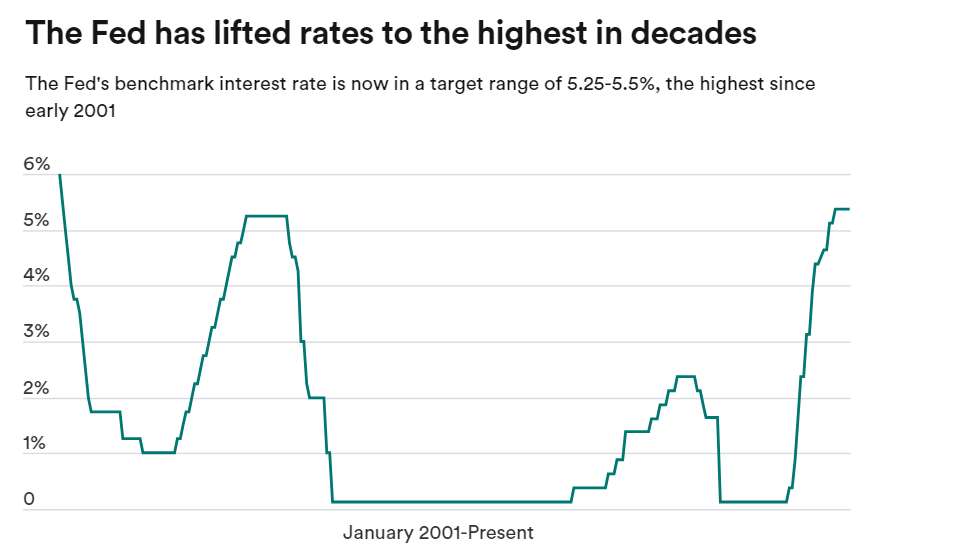

Although the Fed halted rate hikes last summer, it has been stealthily tightening monetary policy by reducing its $7.7 trillion indebted balance and other assets at a rate of $80 billion per month.

This week, officials may start discussing slowing down the pace of balance sheet reduction. Although a policy change isn't imminent, Fed members expressed their wishes last month to clearly communicate any shifts regarding their balance sheets to the public in advance. Earlier this month, Dallas Fed President Kaplan suggested the Fed should first slow down the pace of balance sheet reduction before gradually ending the program.

Macroeconomist Boris Schlossberg of BK Asset Management believes that the discussions regarding the minutes and recent topics by Fed officials mean that reductions in the balance sheet may precede interest rate adjustments and that the discussions on reductions could alleviate the volatility in the interest rate market that has been turbulent over the past year.

Regarding The Future

While interest rate cuts have generally become an industry consensus, the path for future cuts might not conform with the previous two cycles.

During the financial crisis of 2008 and at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the Fed drastically shaved borrowing costs at a lightning-fast pace. But now, with unemployment rates staying at historical lows, robust economic growth, slowing inflation, and seemingly no complaints from consumers about current interest rates, the Fed does not need to lower rates as steeply as before.

With economic activity and labor markets in good shape and inflation coming down gradually to 2 percent, I see no reason to move as quickly or cut as rapidly as in the past, said Fed Governor Christopher Waller in a speech on January 16th. My hope is that the revisions confirm the progress we have seen, but good policy is based on data and not hope.

From a data standpoint, inflation indicators are still higher than the Fed's 2% target. The resistance of consumer data and wage support from the job market might pose some hurdles for future price drops.

Lessons from history, such as the excessive policies in the 1970s when an unexpectedly relaxed monetary policy led directly to legendary inflation, followed by a severe economic recession, remind Powell and his team to tread carefully. They certainly wouldn't want to repeat the missteps of then Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, whose failed policies were enshrined in textbooks as case studies of what not to do.

Expert analysis on U.S. markets and macro trends, delivering clear perspectives behind major market moves.

Latest Articles

Stay ahead of the market.

Get curated U.S. market news, insights and key dates delivered to your inbox.

Comments

No comments yet