The Strategic Implications of Private Equity Involvement in Aging Hydro Infrastructure

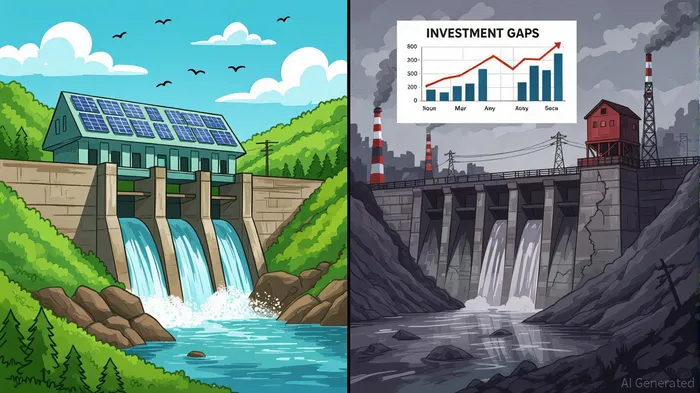

The global hydroelectric infrastructure crisis has reached a critical juncture. Aging dams and hydropower facilities, many over half a century old, are straining under the dual pressures of climate change and insufficient funding. In the United States alone, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) has graded the nation's dams a D+ in 2025, with 92,000 structures facing modernization needs and a $185 billion funding shortfall over the next decade . This crisis is mirrored globally, where hydropower projects in the pipeline total $1.1 trillion but face rising costs and environmental scrutiny . Against this backdrop, private equity's growing involvement in aging hydro infrastructure raises urgent questions: Can private capital mitigate risks while ensuring long-term value creation? How do regulated and private ownership models compare in addressing modernization and sustainability?

Regulated Models: Stability vs. Inefficiency

Regulated hydro infrastructure, typically managed by public utilities or government agencies, prioritizes long-term stability and compliance with safety standards. In the U.S., the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) allocated $3 billion for dam rehabilitation, yet this pales against the $185 billion needed to address aging systems . Regulated utilities often rely on rate cases and debt financing, which face challenges from rising interest rates and regulatory delays . However, these models benefit from centralized planning and alignment with public objectives. For example, Iberdrola's EUR 47 billion Strategic Plan 2023-2025 emphasizes grid modernization and smart infrastructure, demonstrating how regulated entities can integrate renewable energy while maintaining reliability .

Yet, regulated models are not without flaws. Political interference, bureaucratic inertia, and underutilized infrastructure—such as overcapacity in sub-Saharan Africa—highlight inefficiencies in public ownership . In the U.S., the relicensing process for hydropower facilities is notoriously complex, deterring investment and delaying upgrades .

Private Equity: Innovation and Risk

Private equity's entry into hydro infrastructure is driven by its ability to deploy capital rapidly and introduce operational efficiencies. The global infrastructure investment gap—projected to reach $106 trillion by 2040—has made private equity an attractive partner, particularly in developing economies where public funding is scarce . For instance, the Luapula Hydropower Project in Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo employs a blended financing approach, combining concessional loans, commercial funding, and equity to address regional energy poverty .

However, private equity's focus on short-term returns can clash with the long-term nature of hydro projects. The Nam Theun 2 project in Laos, a private-public partnership, faced criticism for opaque financial processes and limited transparency in addressing social and environmental impacts . Similarly, the Bujagali Hydroelectric Project in Uganda, a BOOT (Build-Own-Operate-Transfer) model, encountered cost overruns and delays due to weak upfront planning . These cases underscore the risks of prioritizing profit over sustainability.

Risk Mitigation and Long-Term Value Creation

Comparative studies reveal nuanced outcomes. Regulated models often distribute risks through policy frameworks and public oversight, ensuring consistent investment security . In contrast, private equity projects, particularly in developing economies, rely on Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) to share risks between stakeholders. For example, the Lower Sesan 2 Dam in Cambodia, a private initiative, faced ecological and resettlement disputes, highlighting the need for robust governance .

Long-term value creation in regulated models is tied to strategic planning and cross-border cooperation, as seen in Denmark's wind energy success . Private equity, meanwhile, emphasizes operational efficiency and scalability, as demonstrated by India's focus on rural energy access . Yet, private projects require strong regulatory frameworks to align with sustainability goals. The Mekong Basin's experience shows that private actors often benefit from short-term gains while public institutions bear long-term environmental and social costs .

Sustainability and Modernization: A Delicate Balance

Modernization outcomes depend on the alignment of risk mitigation with sustainability. Regulated systems, such as China's cascade hydropower reservoirs, use systems modeling to balance ecological and energy needs . Private equity projects, like Kenya's green bond-funded initiatives, leverage innovative financing to bridge gaps but must address localized environmental impacts .

The International Energy Agency (IEA) emphasizes that a fourfold increase in transmission and distribution investments is needed to support the energy transition . Both ownership models must adapt: Regulated utilities require streamlined relicensing and public-private collaboration, while private equity must adopt transparent governance and climate-resilient designs.

Conclusion

The strategic implications of private equity involvement in aging hydro infrastructure are profound. While private capital offers innovation and scalability, its success hinges on robust governance and alignment with public objectives. Regulated models provide stability but must overcome inefficiencies. The path forward lies in hybrid approaches: leveraging private equity's agility while embedding sustainability and transparency through regulatory frameworks. As climate change intensifies and energy demands rise, the balance between risk mitigation and long-term value creation will define the future of hydro infrastructure—and the broader energy transition.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios