Reshaping Global Trade: Strategic Diversification in a Polyamorous Era

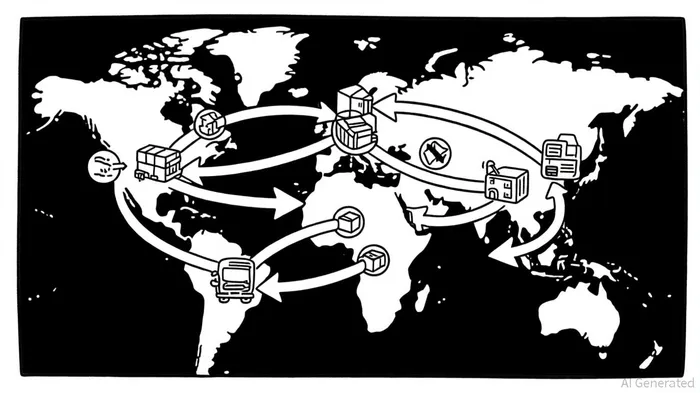

The global trading system is undergoing a seismic shift, driven by geopolitical fragmentation, supply chain vulnerabilities, and the collapse of traditional multilateral frameworks. Michael Froman, former U.S. Trade Representative and current President of the Council on Foreign Relations, has coined the term “polyamorous” to describe this new era of trade—a system where nations form overlapping, fluid partnerships to balance resilience, security, and economic efficiency. This evolution is not merely theoretical; it is reshaping investment strategies, corporate risk management, and the very architecture of global supply chains.

The Polyamorous Framework: From Multilateralism to Plurilateralism

Froman's concept of a “polyamorous” trading system reflects the reality of a world where no single institution or agreement can unify global commerce. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has struggled to mediate disputes in an era of unilateral tariffs and mercantilist policies, while the U.S.-China trade war and Russia's invasion of Ukraine have exposed the fragility of centralized supply chains. In response, countries are embracing open plurilateralism—coalitions of like-minded partners focused on shared goals such as secure supply chains, green technology, and industrial policy[1].

For example, the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) prioritize domestic interests and sustainability over pure economic efficiency, creating a patchwork of trade rules[3]. This shift aligns with Froman's vision of a system where nations collaborate selectively, forming “friendshoring” alliances to mitigate risks from geopolitical rivalries and supply shocks.

Semiconductor Supply Chains: A Case Study in Diversification

The semiconductor industry epitomizes the urgency of strategic diversification. With components traversing over 70 borders before final assembly[1], the sector's reliance on concentrated hubs like Taiwan and South Korea has proven perilous. The 2024-2032 period is projected to see $2.3 trillion in new investments in wafer fabrication, with the U.S. capturing 28% of this capital by 2032—up from nearly zero in 2022[2]. This surge is driven by the CHIPS Act, which incentivizes domestic production, and the “China-plus-one” strategy, where firms diversify into Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe for assembly and packaging[4].

Financial outcomes are mixed. While the U.S. semiconductor industry has secured $348 billion in private commitments through 2030 (supported by $50 billion in federal funding), risks like overcapacity and price pressures loom[4]. However, the long-term goal—reducing reliance on single regions for advanced chip production—aligns with Froman's polyamorous framework, where resilience trumps efficiency.

Geopolitical Tensions and the Cost of Resilience

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has further accelerated diversification efforts. Shipping routes now avoid the Red Sea, with container ships opting for the costly Cape of Good Hope route, pushing shipping costs toward pandemic levels[5]. Energy trade dynamics have also shifted, with Russia pivoting to China and India as key markets. Meanwhile, U.S. firms are leveraging Mexico as a nearshoring hub, prioritizing agility over lowest-cost sourcing[5].

Quantifiable data underscores the financial implications. The IMF notes that diversifying import sources for upstream, shock-exposed goods can enhance resilience but at the cost of efficiency[3]. For instance, a 2025 study found that firms with diversified supplier networks experienced 15-20% faster recovery from disruptions compared to those reliant on single suppliers[1]. However, this resilience comes with higher operational complexity and regulatory compliance costs.

Metrics for Measuring Resilience

Investors must now evaluate supply chain resilience using metrics such as lead time reduction, risk mitigation scores, and absorptive capacity—the ability to withstand shocks without operational collapse[6]. The OECD emphasizes that effective risk management, not retreating from globalization, is key to resilient supply chains[2]. For example, Apple's supplier diversification strategy, which includes shifting production to India and Vietnam, has reduced its exposure to China-specific risks while maintaining 80% of its manufacturing capacity in Asia[5].

The Future of Trade: A Polyamorous Path Forward

Froman's polyamorous framework is not without challenges. Fragmented regulations and rising protectionism could hinder global economic growth[1]. Yet, the alternative—a return to rigid multilateralism—is politically unsustainable in a world defined by strategic competition. The future will likely see a hybrid system: coalitions of nations collaborating on specific issues (e.g., clean energy standards or AI governance) while maintaining strategic autonomy in others.

For investors, this means prioritizing sectors and regions that align with open plurilateralism. The semiconductor industry, green technology, and logistics infrastructure are prime candidates. Companies that successfully navigate this polyamorous landscape—like IntelINTC--, which is expanding in Arizona and Germany, or ToyotaTM--, which has diversified its battery supply chain across Southeast Asia—will outperform peers reliant on outdated models[4].

Conclusion

The polyamorous trading system is not a temporary phase but a structural shift in global commerce. As Froman argues, the new normal demands pragmatism: building coalitions that balance national interests with shared goals. For investors, the key is to align with this reality—supporting firms and regions that prioritize diversification, resilience, and strategic flexibility. In a world of geopolitical uncertainty, the winners will be those who embrace complexity as a competitive advantage.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios