Opportunity Cost and Personal Finance: How Non-Optimal Behaviors Erode Long-Term Wealth

In personal finance, opportunity cost is the silent thief of wealth. It represents the value of what is sacrificed when a decision is made—such as spending on immediate pleasures instead of investing for the future. Recent studies underscore how non-optimal financial behaviors—overspending, high-interest debt, and under-saving—systematically erode long-term wealth, often with irreversible consequences.

The Hidden Cost of Overspending and Under-Investing

Consider a scenario where an individual invests $10,000 in a savings account yielding 3% annual returns instead of a diversified portfolio with an average 7% return. Over 30 years, the opportunity cost amounts to $400 annually, or $12,000 in lost gains, assuming compounding [4]. This example illustrates how low-yield choices, even seemingly prudent ones, fail to harness the power of compounding. For context, a $10,000 investment at 7% would grow to $76,123 in 30 years, while the same amount at 3% would reach only $24,273 [4]. The gap widens further when considering inflation, which erodes purchasing power over time.

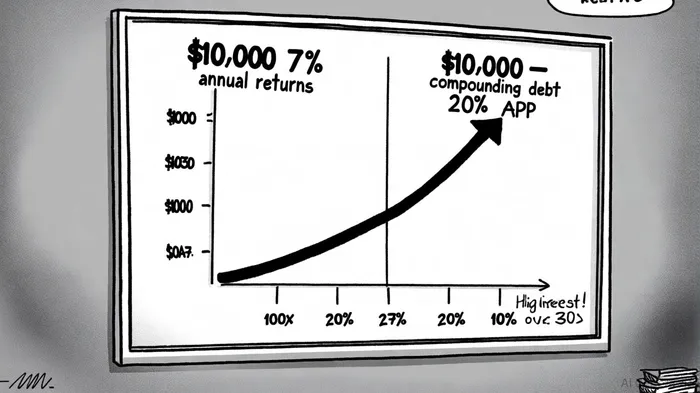

High-Interest Debt: A Drag on Net Worth

High-interest debt, particularly credit card debt, exemplifies the destructive force of opportunity cost. A $10,000 balance with a 20% APR would balloon to $16,192 in three years due to compounding [2]. Over a 30-year horizon, the erosion is even more severe. If that $10,000 were instead invested at 7%, it would grow to $38,697, highlighting a $54,889 opportunity cost [2]. By 2025, 68% of retirees with debt carried credit card balances, with median debt among adults over 50 rising from $55,300 in 2016 to even higher levels [1]. These figures underscore how debt servicing diverts funds from investments, perpetuating wealth inequality.

Under-Saving and the Retirement Crisis

The U.S. faces a looming retirement savings shortfall, with 47% of working households at risk of falling short [1]. For every $1,000 under-saved annually, a 30-year-old worker misses out on $18,892 in retirement savings by age 65, assuming a 7% return [5]. A 2025 analysis projects that insufficient savings could cost state and federal governments $1.3 trillion by 2040, as households rely increasingly on public assistance [1]. This crisis is exacerbated by the shift from employer-sponsored defined benefit plans to employee-managed defined contribution plans, which often lack the guidance to optimize savings [2].

Financial Literacy: A Mitigating Factor

Financial literacy plays a pivotal role in curbing non-optimal behaviors. Studies show that individuals with higher financial knowledge are 30–40% more likely to save adequately for retirement and avoid high-interest debt [3]. For instance, financially literate individuals in India were twice as likely to diversify their portfolios and contribute regularly to retirement accounts [3]. Conversely, overconfidence—often mistaken for financial literacy—can lead to poor decisions, such as underestimating risks or overestimating returns [3].

Long-Term Projections and Policy Implications

Quantitative models reveal the staggering scale of wealth loss. A 30-year projection of high-interest debt's impact estimates a $24,000–$36,000 decline in average household wealth due to inflationary pressures and higher borrowing costs [6]. Meanwhile, under-saving could leave households $7,000 short annually by 2040, forcing reliance on shrinking public safety nets [1]. Policy interventions, such as automatic enrollment in retirement plans and financial education programs, have proven effective in boosting savings rates by 26–91 percentage points [1].

Conclusion

Non-optimal financial behaviors are not merely poor choices—they are systemic barriers to wealth accumulation. By understanding opportunity cost and addressing root causes like financial illiteracy and high-interest debt, individuals and policymakers can mitigate long-term wealth erosion. The data is clear: proactive planning, disciplined saving, and informed investment decisions are the cornerstones of financial resilience.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios