Environmental and Regulatory Risks in Ghana's Artisanal Gold Mining Boom

Ghana's artisanal gold mining sector has experienced a dramatic boom in recent years, driven by soaring global gold prices and the formalization of the industry under the Ghana Gold Board (GoldBod) reforms. While these developments have boosted exports and investor confidence, they have also intensified scrutiny over environmental degradation and public health risks. For investors, the challenge lies in balancing the sector's economic potential with its long-term sustainability amid rising concerns about mercury pollution, deforestation, and regulatory enforcement.

The Environmental and Health Toll of Artisanal Mining

Artisanal gold mining in Ghana has long relied on mercury-based extraction methods, leaving a trail of toxic contamination. According to a 2025 Reuters report, soil mercury levels in mining communities such as Konongo Zongo have reached 1,342 parts per million (ppm), far exceeding the World Health Organization's (WHO) 10 ppm safety threshold[1]. Arsenic levels in the same areas are equally alarming, with concentrations hitting 10,060 ppm—over 4,000% above international guidelines[1]. These toxins pose severe health risks, including kidney failure, neurological damage, and developmental disorders in children. Studies have already documented cases of mercury ingestion among children in mining zones, with some requiring dialysis[1].

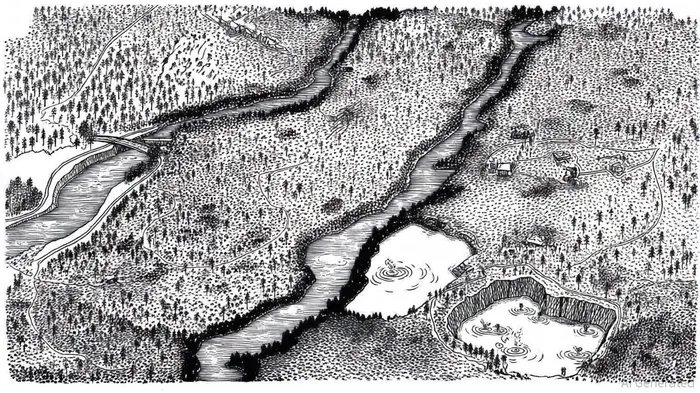

Environmental degradation is equally dire. In the Oda River Forest Reserve, illegal mining activities expanded by 1917.6% between 2018 and 2023, eroding forest cover and biodiversity[2]. Deforestation rates in the region have accelerated, with heavily mined zones now devoid of vegetation[2]. Mercury contamination has also seeped into water bodies and food chains, with lead levels in fish samples surpassing WHO safety limits[1]. These ecological impacts threaten not only local communities but also Ghana's broader environmental goals, including carbon sequestration and biodiversity conservation.

GoldBod Reforms: A Step Toward Formalization and Sustainability

In response to these challenges, Ghana introduced the GoldBod Act in 2025, centralizing control over gold trading and exports under the Ghana Gold Board. The reform aims to curb illegal mining (“galamsey”), enhance transparency, and align the sector with international environmental and ethical standards[3]. By mandating traceability for all gold exports and enforcing licensing requirements, GoldBod has already seen success: artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) gold exports surged to $4 billion between February and May 2025, surpassing large-scale mining for the first time[4].

The board has also prioritized environmental remediation, pledging to reclaim 1,000 hectares of degraded land by late 2025 and launching a National Gold Traceability System to ensure compliance with environmental standards[5]. Additionally, GoldBod's domestic refining initiatives and plans for LBMA accreditation aim to add value to Ghana's gold exports while promoting sustainable practices[4]. These measures have bolstered investor confidence, with foreign stakeholders citing improved regulatory clarity and reduced smuggling risks[5].

Risks and Challenges for Investors

Despite these strides, significant risks persist. Enforcement of GoldBod's regulations remains uneven, with illegal mining operations continuing to displace communities and degrade ecosystems[1]. Mercury use, though targeted by initiatives like the Gold Kacha device, remains widespread due to lax oversight[1]. For investors, this raises concerns about reputational risks and potential regulatory tightening, which could increase compliance costs.

Moreover, the sector's long-term profitability hinges on GoldBod's ability to balance economic growth with environmental stewardship. While the board's traceability system and reclamation projects are promising, their success depends on sustained funding and political will[5]. Investors must also consider the social license to operate: communities affected by mining-related health crises may resist projects perceived as prioritizing profit over public welfare[1].

Conclusion: Navigating a Complex Landscape

Ghana's artisanal gold sector presents a paradox: it is a vital engine of economic growth yet a source of severe environmental and health risks. The GoldBod reforms have made significant strides in formalizing the industry and improving transparency, but their long-term success will depend on rigorous enforcement and community engagement. For investors, the key is to adopt a cautious, long-term perspective. While the sector's profitability is undeniable, those who ignore environmental liabilities or regulatory uncertainties may find themselves exposed to both financial and reputational fallout.

As Ghana's gold boom continues, stakeholders must ask whether the country's gold rush can be reconciled with sustainable development. The answer will shape not only the future of mining in Ghana but also the broader global conversation about resource extraction in the 21st century.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios