First Brands' Collapse: A Harbinger of Shadow Banking Risks in the Private Debt Market

The collapse of First Brands Group in September 2025 has sent shockwaves through the private debt market, exposing systemic vulnerabilities in off-balance sheet financing structures that mirror historical crises like the 2008 subprime mortgage meltdown and the 2021 Greensill Capital implosion. As a $10 billion automotive parts supplier, First Brands leveraged opaque financing mechanisms-including fraudulent invoice factoring, supply chain finance, and special purpose vehicles (SPVs)-to conceal billions in liabilities, ultimately triggering a cascade of defaults and regulatory scrutiny. This case underscores the dangers of unregulated shadow banking and serves as a cautionary tale for investors and regulators alike.

The Anatomy of First Brands' Collapse

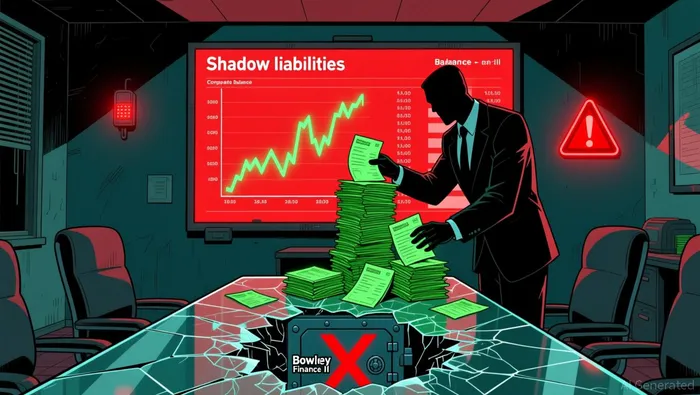

First Brands' downfall was rooted in its aggressive use of off-balance sheet financing, which allowed the company to mask its true debt levels. According to a Bloomberg report, the firm submitted non-existent or inflated invoices-often inflated by hundreds of times their actual value-to secure short-term cash flow. For instance, one invoice was artificially inflated from $179.84 to $9,271.25. These fraudulent practices, coupled with the creation of a "slush fund" called Bowery Finance II, enabled founder Patrick James to siphon over $700 million between 2018 and 2025.

The company's debt structure was staggering: according to financial reports, $6.1 billion in on-balance-sheet obligations, $2.3 billion in off-balance-sheet financing, $800 million in supply chain liabilities, and $2.3 billion in factoring liabilities. A forensic audit by Alvarez & Marsal revealed that SPVs, which were supposed to hold cash, had "no cash in them," exposing the fragility of the firm's financial engineering. This opacity eroded creditor confidence, prompting a U.S. Trustee to demand an independent investigation into the missing $2.3 billion.

The company's debt structure was staggering: according to financial reports, $6.1 billion in on-balance-sheet obligations, $2.3 billion in off-balance-sheet financing, $800 million in supply chain liabilities, and $2.3 billion in factoring liabilities. A forensic audit by Alvarez & Marsal revealed that SPVs, which were supposed to hold cash, had "no cash in them," exposing the fragility of the firm's financial engineering. This opacity eroded creditor confidence, prompting a U.S. Trustee to demand an independent investigation into the missing $2.3 billion.

Parallels to Historical Crises

First Brands' collapse echoes the 2008 subprime crisis and the Greensill Capital debacle. Like subprime mortgage-backed securities, First Brands' fraudulent invoices were repackaged as collateral for financing, creating a false illusion of value. Similarly, Greensill Capital's supply chain finance model relied on opaque receivables, which collapsed when underlying assets were scrutinized. In both cases, the lack of transparency and regulatory oversight allowed risks to accumulate undetected.

The 2008 crisis demonstrated how interconnected financial institutions could amplify systemic risks. First Brands' failure has similarly exposed vulnerabilities in the private credit market. Major banks like Jefferies and UBS O'Connor faced significant exposure-$715 million and 30%, respectively-through the firm's complex debt web. This interconnectedness raises concerns about contagion, as highlighted by the Federal Reserve, which warned of "moderate vulnerabilities" in the middle market due to opaque off-balance-sheet funding.

Systemic Risks in the Private Debt Market

The private credit market, now exceeding $2.1 trillion in assets under management (AUM), has grown rapidly post-2008 as traditional banks faced stricter capital requirements. However, this growth has come at a cost. A report by The Analysis Series notes that middle-market borrowers often operate with leverage ratios (1.8x to 2.0x) that leave little buffer against economic shocks. Additionally, the proliferation of "Cov-Lite" and "Cov-Loose" loan structures-where covenants are weak or absent-has reduced lenders' ability to intervene before defaults occur.

Regulators are increasingly concerned about the sector's interconnectedness. Over $95 billion in committed credit lines from traditional banks to private credit funds highlight the potential for a domino effect during a crisis. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned that the deepening ties between private credit and banks could act as a "locus of contagion" in future crises.

Regulatory Responses and Lessons Learned

Post-2008 reforms, such as Basel III, focused on traditional banks but left non-bank lenders in a regulatory gray area. The Greensill and First Brands collapses have forced regulators to confront this gap. The U.S. bankruptcy court's $7 million probe into First Brands' fraud and the Fed's push for continuous collateral monitoring are steps toward addressing these risks. However, experts argue that more granular data reporting, stricter underwriting standards, and enhanced servicing oversight are needed. As noted by The National News, "the next financial crisis may lurk in the shadows of unregulated private debt markets." Investors must demand greater transparency, while regulators should consider extending prudential tools-such as liquidity restrictions and stress tests-to non-bank intermediaries.

Conclusion

First Brands' collapse is not an isolated incident but a symptom of deeper flaws in the private debt market. Its reliance on opaque off-balance-sheet structures, fraudulent invoicing, and weak covenants mirrors historical crises, underscoring the need for systemic reforms. As the sector continues to grow, stakeholders must prioritize risk management, transparency, and regulatory oversight to prevent another shadow banking meltdown.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios