Three 401(k) Mistakes That Could Cost You a Lifetime of Wealth

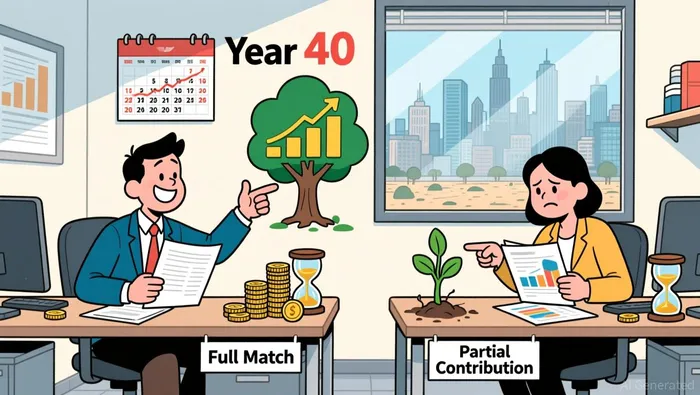

The single biggest mistake in a 401(k) is failing to contribute enough to capture the full employer match. This isn't just a missed annual bonus; it's a surrender of guaranteed, compounding returns that can create a substantial lifetime wealth gap. Think of the match as free money, and then compound that free money for decades.

The math reveals the true cost of overlooking this opportunity. Consider the case of someone who leaves $1,000 in matching dollars on the table for 40 years. Applying a conservative 8% annual growth rate-below the long-term average of the stock market-that single forfeited amount would grow to nearly $22,000. The impact is even more dramatic when the forfeited sum is larger. If an employer matches 100% of the first $3,000 contributed, and an employee only contributes $1,000, they give up $2,000 in immediate match. Forgoing that $2,000 in a 30-year retirement horizon could mean $20,000 less at retirement.

This is the essence of a compounding advantage. The employer match provides a direct, risk-free return on your initial contribution. By not taking it, you're effectively turning down a guaranteed rate of return that then sits idle, while the money you did contribute continues to grow. The gap widens over time, not just in absolute dollars but in the potential income stream it could have generated in retirement. For all the complexity of investment choices, the first and most critical decision is to claim every dollar of this free money.

Experts agree that giving up any portion of your 401(k) match is a big mistake. In fact, one study cited by financial analysts shows that this one seemingly simple error could cost an investor over $300,000 in lifetime retirement wealth. That figure underscores the profound, long-term damage done by a single, avoidable choice. The lesson is clear: the employer match is a guaranteed return that compounds into a substantial lifetime wealth gap if left behind.

The Hidden Tax Trap of Ignoring Roth Options

The third major error is passing up a Roth 401(k) option when it's available. This isn't just a matter of choosing between a tax break today and a tax break tomorrow. It's a fundamental decision about long-term tax efficiency and compounding power.

The core difference is straightforward. With a traditional 401(k), you contribute pre-tax dollars, reducing your current taxable income. But you'll pay income tax on every withdrawal in retirement. A Roth 401(k) works the opposite way: you contribute after-tax dollars, so you get no immediate tax break. The trade-off is that your investments grow tax-free, and qualified withdrawals in retirement are also tax-free. This creates a powerful compounding advantage over decades.

The key insight is about locking in your tax rate. You're essentially betting that your tax rate in retirement will be lower than it is now. But that's a risky assumption. Tax rates can change, and your retirement income-potentially from multiple sources like Social Security, pensions, and required minimum distributions (RMDs)-could push you into a higher bracket. By choosing a Roth, you lock in today's tax rate on that money. As one analysis notes, you're at least locking in today's tax rate on that money. This is a form of tax rate insurance for your future self.

The tax-free growth and withdrawals are the real amplifiers. Every dollar you save in a Roth 401(k) compounds without the drag of future capital gains or income taxes. This is especially valuable for younger workers with a long time horizon. The longer the money sits, the more the tax-free compounding can work in your favor.

There's also a significant flexibility advantage. Traditional retirement accounts mandate RMDs starting at age 73, forcing you to take taxable withdrawals even if you don't need the money. Roth 401(k)s do not have this requirement. This gives you more control over your retirement income and tax planning. As the analysis points out, Roth 401(k)s don't force you to take required minimum distributions, offering more options when you're ready to retire.

For many, the decision isn't all-or-nothing. You can contribute to both a traditional and a Roth 401(k) within the same plan, creating a diversified tax position in retirement. The bottom line is that overlooking the Roth option means leaving a powerful, tax-efficient compounding engine on the table. It's a long-term choice where the efficiency of each dollar saved is magnified by the absence of future tax liability.

The Behavioral Biases That Sabotage Your Plan

The most expensive 401(k) mistakes are often not about financial knowledge, but about human nature. Psychological biases and poorly designed plan structures create powerful forces that pull savers away from their long-term goals, locking in losses and missing out on decades of compounding.

One of the most pervasive issues is inertia. When people change jobs, they often roll their 401(k) into an IRA, but then fail to make any investment decisions. According to a Vanguard study, nearly a third who rolled savings into IRAs at Vanguard in 2015 still had the balance sitting in cash seven years later. This isn't a strategic choice; it's a default state. The money sits idle, missing years of market gains. The study estimates this cash-heavy behavior costs Americans more than $172 billion a year in retirement wealth they could have generated by investing in stocks and bonds. The problem is structural: many are accustomed to their savings being automatically invested in a company plan, and the sudden need to actively choose new investments creates a paralysis.

This inertia is compounded by the powerful "disposition effect" and panic-selling during volatility. The human brain is wired to feel losses more acutely than gains-a concept known as loss aversion. When markets dip, this can trigger a panic response. As one analysis notes, the urge to staunch the bleeding can be overwhelming, leading investors to sell into a falling market. This action locks in losses and disrupts the compounding process. The cost is staggering. A study comparing buy-and-hold investors to those who sold after downturns found that the latter, despite starting with the same contributions, would have accumulated $3.6 million versus $6.1 million for the patient investor. The market may feel like it could go to zero, but history shows it eventually recovers.

Finally, the very design of the plan shapes behavior. The difference between an "opt-in" and an "opt-out" system is a classic example of choice architecture. As one analysis explains, if a sponsor designs a 401(k) plan requiring participants to opt-in, typically 20 to 40 percent of the population will not participate. An opt-out design dramatically increases participation. This is because inertia is a powerful default. Similarly, cognitive biases like negativity bias-our natural tendency to focus on potential dangers-can make investors perceive the market as riskier than it is, encouraging them to sit on the sidelines or cash out altogether. As a behavioral scientist at Fidelity notes, the tendency to focus on negative aspects of a situation may be hardwired. These biases are not flaws to be ignored; they are forces that must be anticipated and managed through disciplined plan design and personal awareness.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios